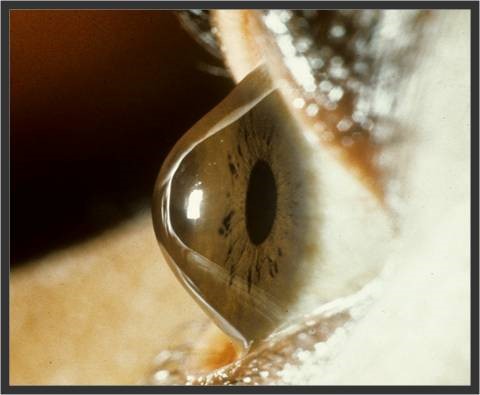

Keratoconus is a disease in which the cornea (the clear front window of the eye) progressively thins and begins to bulge and protrude (see image below). These ‘wonky windows’ cause irregular astigmatism, where the unusual shape of the cornea causes the light to bend as it passes through, resulting in blurred vision. If left untreated, keratoconus can lead to severe vision impairment.

Figure 1: Side view of a normal cornea (left) and Keratoconus (right) showing anterior protrusion of the cornea.

It affects up to 1 in 500 people and primarily people in their teens, thereby impacting on quality of life for the duration of their life. In the early stages of the disease, keratoconus is managed with contact lenses. While this improves vision in the short-term, it does not prevent progression. The ultimate treatment for advanced cases is a corneal graft, in which the abnormal cornea is excised and replaced with donor tissue. Patients require lifelong follow-up and there is a risk of graft failure from immune rejection of the donor tissue, with subsequent grafts having an increased risk of rejection. Collagen crosslinking, which increases the stiffness of the cornea, has been introduced as a treatment with reported success in slowing progression. However, the procedure is only suitable for keratoconus patients at the early stages of disease, and long-term outcomes are not yet known.

Despite the increasing prevalence of keratoconus, the etiology of the condition and the ways to prevent it are largely unknown.

At the Centre for Eye Research Australia, my research team and I conducted the “Australian Study of Keratoconus” looking at over 400 patients with keratoconus to try to better understand the factors associated with the condition to develop strategies that can halt the disease progression or delay the time to first graft. Our data shows that keratoconus poses a significant economic burden to the patients and that the quality of life in these patients is lower than those in patients with later onset eye diseases such as age-related macular degeneration or diabetic retinopathy, highlighting the significant long-term morbidity associated with keratoconus. Imaging of the cornea has demonstrated that the thickness of the cornea at different locations is an important parameter for detecting subclinical keratoconus (disease that shows no clinical signs and symptoms) and that the cornea thins with increasing disease severity.

To take this research further and to unify sample and variable collection across multiple sites, my colleagues at CERA and I are establishing the Keratoconus International Consortium (KIC), incorporating research centres across Australia, Asia, USA and Europe. The consortium will set up a centralised data collection method with the overarching goal of identifying risk factors involved in causation, progression and response to treatment of keratoconus. The establishment of the KIC will have a profound impact on the early detection and management of the disease.

Also we have previously confirmed the influence of genetics on keratoconus and now wish to identify genes directly implicated in disease. For this we are collecting corneal tissues from keratoconus and non- keratoconus patients and using novel genetic technology to determine the specific genes associated with keratoconus. Corneas from keratoconus patients will be collected during corneal transplantation, as they are typically discarded post-surgery. Normal corneas will be collected from eyes undergoing enucleation due to non-corneal conditions such as ocular melanoma.

We would like to take this opportunity to invite volunteers with keratoconus and their family members to participate in our studies. If you agree to take part in this study you will be invited to undergo an eye examination and donate a small blood sample at the Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital, East Melbourne. We are also collecting corneal buttons (which would otherwise be discarded) from keratoconus and non-keratoconus subjects during corneal surgeries. Please contact us before undergoing the surgery if you wish to donate the tissue. Your help will allow us to advance our understanding of keratoconus as well as helping others.

For more information or for an appointment you can contact:

Dr Srujana Sahebjada

Centre for Eye Research Australia

E-mail: genes.study@gmail.com

Mobile: 0433251407